In a society driven by capitalism, the notion of creating wealth from worthless things seems absurd. Is this even possible? The answer is yes. The truth in this statement is a consequence of the cause of economic growth, which has remained a mystery since the publication of Adam Smith’s landmark book, The Wealth of Nations, in 1776.

Something is missing in economic science

The mistake too many economists make is they associate anything that affects economic growth with the cause of growth. They build mathematical models using such causes so that they can make predictions of economic growth. To do this, they need causes that can be quantified in some way. However, suppose the actual cause cannot be quantified. What if the real cause has no commercial value, i.e., it’s worthless. The purpose of this essay is to convince you of this basic fact.

If we want to replicate the result of strong and sustained economic growth, powerful enough to change the world, we need to identify the actual cause. This discovery can create a beneficial cause and effect relationship that could enable prosperity to continue for future generations. To determine the exact cause, we need to question certain assumptions.

There are popular books, such as The Rise and Fall of American Economic Growth by Robert Gordon, that presents a very bleak picture of future U.S. economic growth. Gordon’s observation is that since the 1970s, America has been practicing a form of incrementalism. He alleges that there are no unique inventions today, which have a consumption scale comparable to the historical examples of electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communications. Gordon suggests that we are likely on a path to further economic decline and possibly stagnation. However, his work indicates that the development and application of technology created extraordinary economic growth and wealth over the last 200 years. So, is technology the cause of economic growth, or is there something before it that caused its creation?

Another popular book, The World is Flat by Thomas Friedman, argues that the traditional competitive advantage of knowledge and innovation is shrinking because of modern communications. Once someone has demonstrated something based on established knowledge, another person on the other side of the globe can rapidly imitate or reproduce it. Taken to its logical conclusion, this can eventually lead to a paradox where there will be no incentive to create anything because of the risk to the recovery of the original investment. Here, Friedman focuses on the process of innovation, which transforms inventions into technologies for various applications.; however, are inventions and the process of innovation the actual cause of economic growth, or is there something before them that caused their creation?

These books identify significant trends that may portend a future of limited economic growth; however, they fall far short of identifying the actual cause of economic growth.

The closest economists have come to the resolution of this mystery is the work of the Nobel Prize economist Paul Romer, described in David Warsh’s book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A story of economic discovery.

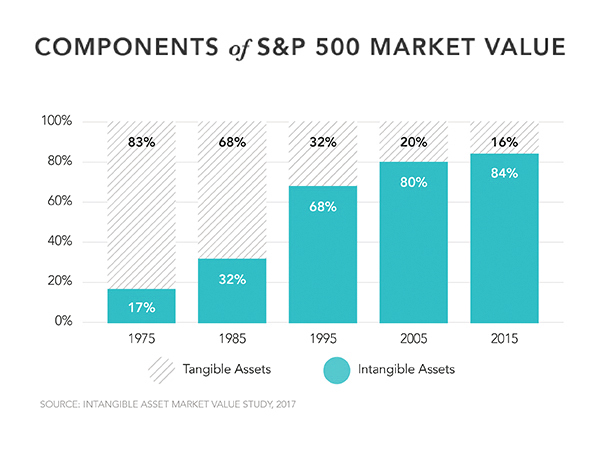

Romer’s work provides a hint as to the cause of economic growth. He identifies the key driver of economic growth to be what the financial world refers to as intangible assets. More specifically, Romer identifies knowledge in the form of a critical commodity, intellectual property (IP), such as patents, mathematical algorithms represented in business processes, and knowledge derived from research and development. These IP assets enable businesses to run and grow through the education and training of people who exploit them, much like factory workers utilize production machinery. There are good reasons to believe in this idea because of the assessed worth of companies depends on intangible assets as indicated by the Standard and Poor’s Stock Index of 500 companies below. Intangible assets directly contribute to the sale price of businesses in the competitive marketplace.

Surprisingly, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (USBEA), which keeps our nation’s financial books, since 2013 includes government and private sector intangible assets of various types in U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) estimates. The assigned asset value is equal to the cost to produce them, which is basic bookkeeping. The USBEA has even revised U.S. GDP estimates back to 1929. However, this assignment of value, if taken too seriously, could cause one to conclude that the total monetary value of Newton’s Laws of Motion, his Law of Universal Gravitation and his creation of

Calculus is equal to his salary at Trinity College. This, of course, would be absurd, however, this begs the question: What is the commercial value of Newton’s discoveries? Unlike IP, intangible assets of this type have no commercial value because they cannot be owned, replicated in quantity to be sold or modified to suit specific applications. However, their economic effects have been profoundly and substantially important to world economic growth over the last 200 years.

Typical descriptions of the cause of the rapid growth in the standard of living that started toward the end of the 18th century appear to be missing something. Did technology cause this growth as we typically learn in history class? Or were there human activities prior and after the start of the British Industrial Revolution that had no commercial value, which caused and sustained this extraordinary period of economic growth? Did something similar happen that transformed the U.S. into the major world economic and military power after WWII? What caused the chemical revolution, the development of heat engines, the electrification of the world, and the digital, communication, and biotechnology revolutions?

The missing piece of the puzzle

In my career leading technology organizations, I have experienced how strong economic performance depends on knowledge derived from research and development. I also understand how the true trailblazers that acquired great wealth depended on technology revolutions caused by the discovery of unique materials and new scientific, engineering, and mathematical knowledge. Like Newton’s Laws and his Calculus, these discoveries also have no commercial value, i.e., they are worthless things. However, it’s these assets that expand human imagination through education that inspire unique inventions. Inventions are then adapted over time through new materials and innovation to numerous technological applications. It’s the downstream business activities of the private sector that strive for efficiency in the production of products and services to make a profit while limiting their technical, financial, and market risks.

To establish discovery as the actual cause of economic growth, we need to go back in history to identify those things that inspired technology revolutions. Through the threading a set of unrelated events involving people in history who discovered unique materials and knowledge, we can establish recurring patterns. Then by connecting each thread to those things we hold dear today, we will have found the cause of technology revolutions. Such threads take the form of unpredictable recurring patterns in history. They account for wealth creation through technology revolutions during the British Industrial Revolution and how the U.S. became a world economic and military power after World War II. We owe the discovery of these intangible assets to investments in human curiosity by governments and wealthy patrons throughout human history.

Antonine-Laurent de Lavoisier, and

his student E. I. du Pont, the founder

of DuPont.

As an example, consider the mysterious force of the ancient world, fire. The scientific explanation of this strange phenomenon as a chemical reaction occurred during the 18th century. This explanation gave birth to modern chemistry that provided the rules for chemical reactions, explained the relationship between the fundamental chemical elements and compounds, and eventually led to the discovery of the 98 natural elements of the Periodic Table. These rules had no commercial value.

As modern chemistry and chemical engineering evolved, many unique materials were discovered, created, and produced in mass quantities for worldwide consumption. Today there is an astounding number, more than 10 million known chemical compounds, or an increase of 20 million percent since 1800. New knowledge, an intangible asset, enabled the creation of the worldwide chemical industry worth over $4 trillion in revenue generated each year. A small investment in human curiosity by the French Government to understand the nature of fire led to an explosion of wealth through a technological revolution. The heat engine, electrification, communication, digital, and biotechnology revolutions were followed similar patterns in human history involving worthless things.

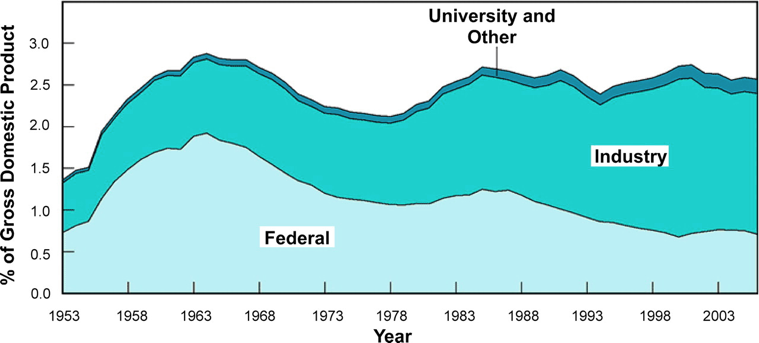

After World War II, U.S. government investment in research and development as a percentage of GDP increased by 200% up until about 1965. This investment expanded the frontiers of science, engineering, and mathematics, and expanded access to quality education for many while taking advantage of the accumulation of knowledge from earlier investments by other governments and wealthy patrons in history. We are still improving upon the results of that investment to this day. To put it in Wall Street terms: Investments

by governments and wealthy patrons over centuries in the discovery of new knowledge about the natural world — i.e., worthless things — has been a tremendously successful strategy for world economic growth.

Despite this success, since around 1965, Federal investment in R&D as a percentage of GDP has declined by 65%. This decline has been a huge opportunity-loss for the American people to create their future, which has impacted economic growth.

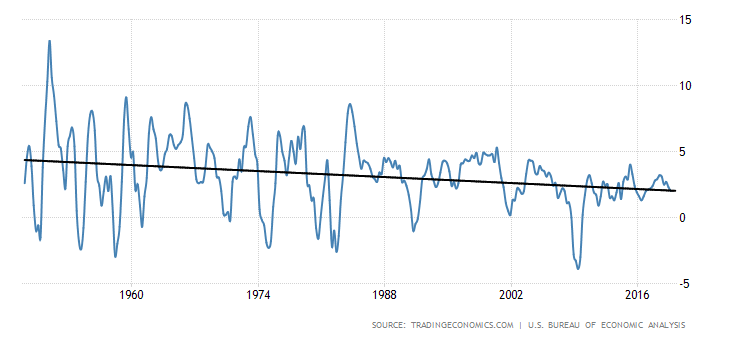

One measure of trends in economic growth is the annual GDP growth rate. This rate, depicted below, has significantly declined over the last forty years. A simple inspection

of this graph reveals that from 1950 to 1980, the GDP growth rate exceeded 5% about twenty-times while after 1980 there were only two excursions above 5%. Just imagine that Federal R&D spending before 1980 and after WWII did not happen, and prior investments by other governments, especially those of Europe, also did not occur. The technologies revolutions we are living off today would not exist because they are all traceable to the discovery of new materials and new knowledge that was primarily funded by governments and wealthy patrons throughout history. To further economic growth, we must invest in the discovery of more worthless things. That is what history teaches us. However, economists are unlikely to accept this because this cause is not quantifiable.

Nevertheless, if policymakers and economists are looking for a fundamental cause for limited economic growth or, worse yet, stagnation, then they need to look into the origins of this decline and the potential consequences of it for the future of our nation.

For further reading, see the related articles:

Making Technological Miracles, Mark P. Mills, The New Atlantis, Spring 2017.

Basic Research and the Innovation Frontier, Mark P. Mills, February 2015, Manhattan Institute

Fund the magic of new science, by Mark P. Mills, June 7, 2015, USA Today